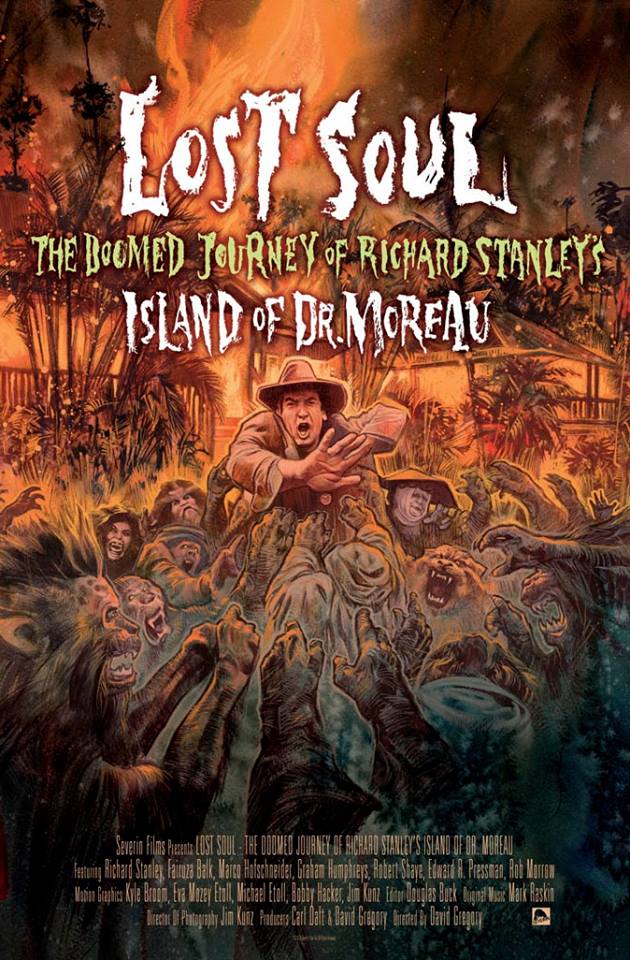

There are few things more intriguing than documentaries about doomed film productions, and we’ve seen a handful of them come out in recent years – from Lost in La Mancha to Jodorowsky’s Dune. With Lost Soul, filmmaker David Gregory paints a portrait of the madness that resulted in one of the oddest exports of the 90s, and it’s as fascinating an account of the filmmaking process as you will likely ever see.

Though he has somewhat dropped off the face of the Earth in recent years, British filmmaker Richard Stanley was once a hot commodity on the scene, impressing with the independently-made Hardware and following it up with 1992’s Dust Devil. A longtime fan of the novel, a proper film adaptation of The Island of Dr. Moreau was a true passion project for Stanley – one that he began developing long before any studio was involved.

Enter New Line Cinema, commonly referred to as “The House that Freddy Built.” The company picked up Stanley’s script and put the wheels in motion, and though they almost immediately ousted Stanley from the director’s chair, in favor of Roman Polanski, fate reunited Stanley with Moreau, and he was tasked with directing the film. It seemed that all the stars were aligning to allow Stanley to live out his cinematic dream, though it wasn’t long before it became one big nightmare.

Problems plagued the production from the outset, including severe weather conditions and unruly actors – Val Kilmer, cast as Montgomery, was a particular thorn in Stanley’s side. More than anything, it seems as if the massive weight of pressure that came along with helming a big Hollywood production was Stanley’s downfall, as he was essentially driven mad by the out of control conditions and was soon excised from his passion project – replaced by John Frankenheimer.

The first half of Lost Soul is all about Stanley’s involvement in the project, and it’s one of the most downright depressing portraits that has ever been painted of the filmmaking industry. In the horror genre especially, it’s quite common for successful independent filmmakers to be adopted by Hollywood and tasked with directing Hollywood films, and those filmmakers tend to completely lose themselves in the process – the studio is often pulling all the strings, in these situations.

More than anything, Stanley’s trials and tribulations on the set of Moreau reflect the damaging nature of studio interference, highlighting the way a project can quickly be derailed by both studio pressures and the various egos that come along with making a Hollywood film. It’s heartbreaking to watch a man so passionate about a project lose sight of his vision and get replaced on his own movie by a filmmaker who had very little passion for it, but that’s all too often the truth of Hollywood.

The enigmatic and thoroughly entertaining Stanley is mostly absent from the second half of Lost Soul, just as he was mostly absent from the majority of the production being highlighted in the doc. From that point forward, it’s tales of the late Marlon Brando’s notoriously trollish behavior that keep Lost Soul as fascinating as possible, as those stories all but confirm that Brando had only one thing in mind, on the set of Moreau: to totally derail the film and have as much fun as possible at the expense of everyone else involved.

Nearly all of the main character’s bizarre qualities were a product of Brando’s whacky imagination, with things like the infamous ice bucket hat and painted face representing the legendary actor’s penchant for being a total nutcase. Whenever he made a suggestion, Brando got his wish, with the demands from both him and the equally unprofessional (but less charming) Val Kilmer resulting in Stanley’s script being almost entirely rewritten – often on the spot.

The end result of years of work on the part of Stanley was of course a wildly ridiculous film that belongs in the annals of the ‘best worst movies’ ever made, one that Stanley ended up having very little to actually do with. In fact, without spoiling the entire story, Stanley’s direct involvement boiled down to little more than an unapproved cameo as one of the half-man/half-animal monsters, bringing his journey full circle in a way that he so eloquently describes in the doc.

A tale of sex, drugs, massive egos, stifled creativity and witchcraft – yes, witchcraft – Lost Soul is quite frankly a Hollywood tale unlike any other. What should’ve been Stanley’s ticket to stardom and creative fulfillment ended up being his downfall, and though his story is ultimately a tragic one, the silver lining is that it has, all these years later, served as the basis for one of the most entertaining documentaries ever made about film and filmmaking.

It’s of course impossible to say whether or not Stanley’s Island of Dr. Moreau would’ve been any better than director-for-hire Frankenheimer’s, though we may actually find out. Stanley says that the documentary has generated lots of interest in his original script, which could someday give him a second chance at making his dream project. The 1996 adaptation was the last we’ve seen of Wells’ novel on the big screen, so needless to say it’s high-time for another trip to the island.

My fingers are crossed for you, Richard.

Support Halloween Love

If an item was discussed in this article that you intend on buying or renting, you can help support Halloween Love and its writers by purchasing through our links:

(Not seeing any relevant products? Start your search on Amazon through us.)